Published in Unique Estates Life Magazine Winter 2024.

One of the most successful exhibitions from London's Victoria & Albert Museum, "Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto," has been touring the world for three years. The final stops on the tour are Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Sydney.

The ambitious task of the curators, who assembled the creative framework of the exhibition, is to reveal the secret behind the success of the controversial figure Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel (1883 – 1971), widely acknowledged as the most influential woman in the history of fashion. For six decades, she achieved total triumph in the decidedly male world of haute couture, establishing herself as a leading figure who changed not only fashion trends but also high society life in Paris and around the world. Chanel is synonymous with elegance, classic style, and irresistible, timeless charm. In an effort to explain the magnetic character of the creator of Chanel and the variety of activities surrounding the brand, the team at the London museum traces the stages of the company's evolution and the global fashion industry.

She was known as a daring and free-spirited woman who didn't tolerate limitations. This was one of the reasons she approached her fabric choices with boldness, unexpectedly incorporating otherwise very common materials. Such is the story of jersey, which Coco paved the way for in fashion. This relatively cheap and very ordinary fabric, used primarily for men's and women's underwear and hosiery, completely changed its status thanks to Coco's idea to include it in her collection. She used knitted jersey for her debut, which gave her clothes a flowing and flexible quality. Soon after, the fabric that everyone had once looked down on became a synonym for elegance. The fashionable French seaside resorts of Deauville and Biarritz embraced her bold idea, and although fashion journalists were initially suspicious of the simple material that had somehow snuck into fashion through the back door, in November 1916, American and British Vogue announced that "Chanel is a master of her art, and it lies in jersey."

Black has been a signature for Chanel since the late 1910s, when it was typically seen as a color for uniforms. In 1926, Gabrielle introduced the little black day dress made from Chanel's crépe de chine, and ladies from all over the world went crazy for it. The media dubbed it "the Ford of fashion," and in Chanel's atelier, its code name was LBD (little black dress). At a time when women changed clothes several times a day for different occasions, the LBD's versatility made it a huge hit. The color black was Coco Chanel's territory, and over the years, she interpreted not only its shades but also its forms and fabrics in different ways. The fashion house's archives in Paris hold dresses and jackets made from black silk crêpe, silk chiffon, satin, silk velvet, and georgette. However, her undisputed favorite was black lace, which was used to create the cocktail and evening dresses included in her 1956 collection.

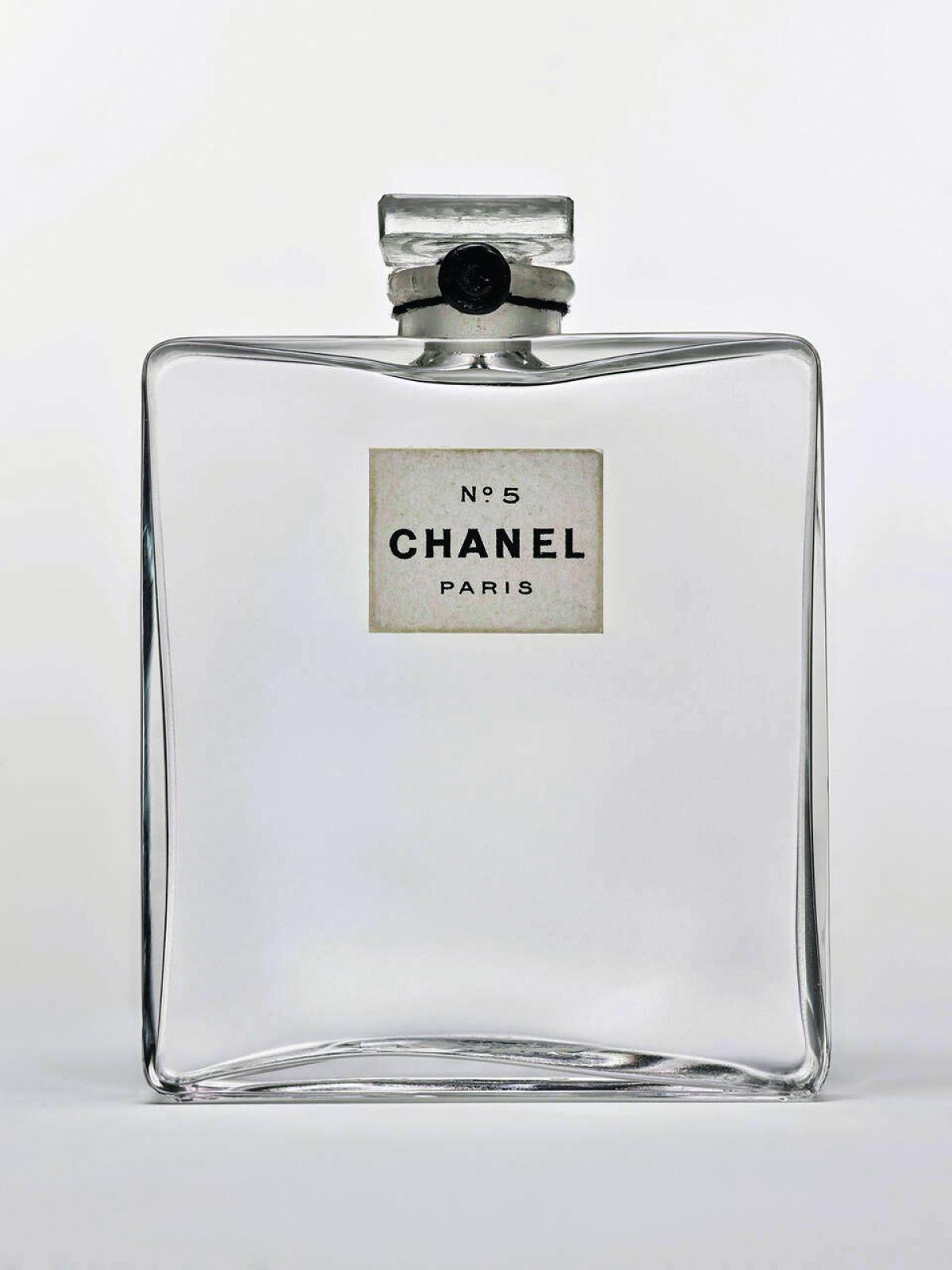

Ever since its creation in 1921, CHANEL №5 has been the crown jewel of the empire. Designed as an extension of her clothing and her sense of modernity, it came as no surprise that Gabrielle Chanel drew inspiration from herself. The French perfumer Ernest Beaux, a Russian-born artist who had previously supplied the Russian Imperial Court with original scents, presented her with №5—a unique fragrance made from over 80 ingredients, including jasmine, ylang-ylang, sandalwood, May rose, and neroli. Initially, Beaux showed her ten samples, and Gabrielle Chanel chose number five: her favorite number and the perfect name for the scent. The secret of №5 lies in the experimental use of aldehydes (organic chemical compounds), which Beaux used in large quantities, combining them to create an abstract and incredibly modern perfume for its time. The resulting fragrance had no hint of the typical floral notes of the era, setting it apart from anything else in women's perfumery.Coco also broke from the norm by seeking original and unexpected ideas for the perfume's glass bottle. Unlike the highly decorative, Art Nouveau-inspired bottles from other perfumers, she chose a simple, square bottle reminiscent of medicine vials or men's cologne bottles. Despite minor modifications, the bold, clean design with a minimalist, almost white label and black lettering remains largely unchanged today.In the same way, the formula for CHANEL №5 has remained the same since Ernest Beaux first created it over a century ago, with the woman Coco Chanel in mind. "№5" would become the best-selling fragrance in the world and remains a bestseller to this day. The late British Queen Elizabeth II used only this perfume, and the fragrance's most beautiful face, Marilyn Monroe, famously stated in an interview that she wore nothing but Chanel №5 to bed.

In the 1920s, Gabrielle revolutionized fashion once again by introducing the tweed suit, elevating it from its traditional status as sportswear. The Chanel suit, presented at the 1954 fashion show, became synonymous with the brand's timeless elegance. Its creation followed her design manifesto: clothes should be elegant yet easy to wear, balancing comfort, simplicity, and style. Coco's preferred elastic fabrics and cardigan-like cut for the jacket provided much greater freedom of movement, and the CHANEL suit naturally became a favorite of famous women in the 1950s and 60s. Renowned Chanel clients at the time included Princess Grace of Monaco, Elizabeth Taylor, Jacqueline Kennedy, and Marlene Dietrich. None of them missed the VIP fashion shows on Rue Cambon in Paris. Hollywood actress Lauren Bacall ordered this pink-beige tweed suit from the Chanel Spring/Summer 1959 collection. It featured many of the classic suit's typical characteristics: a straight-cut jacket, a matching jacket and blouse lining, gilded buttons with a lion's head motif, and a gilded metal chain sewn into the jacket's hem to ensure the fabric fell perfectly.

Accessories were fundamental to Gabrielle Chanel's concept of a harmonious silhouette. They reflected her pragmatic vision of fashion and introduced recognizable luxury codes that highlighted the specificity of her style. After its introduction in February 1955, the 2.55 bag (named for the month and year it was created) quickly became another sought-after Chanel classic. It was offered in three different sizes, made from lambskin, jersey, or silk satin. The design featured a flap with a rectangular turn-lock closure and two sets of grommets that made the metal strap adjustable, allowing it to be worn by hand or over the shoulder. To mark the 50th anniversary of the 2.55, Chanel's creative director at the time, Karl Lagerfeld (1933 – 2019), reinterpreted the original design.

In 1962, Gabrielle Chanel chose the shoemaker Massaro to develop the ultimate Chanel shoe. Founded in 1894, the House of Massaro was a sanctuary of luxury. Their fame naturally reached Coco's ears, and she gave them the nearly impossible task of creating something uniquely special for Chanel and, of course, for herself. She chose beige leather to match her skin tone, thereby lengthening her leg. The small black cap toe created a visual "punctuation mark" on the toes, which shortened the foot and protected the lighter leather from scuffs. The elastic strap and low heel ensured comfort and ease of movement. It's no secret that at the time, many of Chanel's VIP clients would order separate pairs of shoes from their own cobblers to have different colors to match each of their outfits.

Imitation pearls became a hallmark of Chanel, used in necklaces, brooches, or as buttons on suits. In 1931, Vogue declared in its pages that Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel was "responsible for the fashion of faux pearls." Thanks to her, costume jewelry began to be taken seriously in fashion. Gabrielle Chanel's boutiques offered a dazzling range of costume jewelry to be combined with the brand's clothing. Key motifs like flowers, sheaves of wheat, stars, and the sun regularly appeared in her jewelry collections. The lion's head (a nod to her zodiac sign, Leo) was stamped on medallions, brooches, and collars. Gabrielle worked with some of the best jewelry designers and manufacturers in Europe to create her collections, including Count Étienne de Beaumont in the 1920s, Maison Gripoix in the 1930s, Fulco di Verdura in 1933, and François Hugo in the late 1930s.

One of Mademoiselle's favorite models, Jackie Rogers (1931–2023), recounts her time in the Chanel atelier in Paris:

‘Chanel was born in 1883, though she constantly lied about her age. By the time I met her, she had already lived an incredible life and would happily tell me all her stories about men, especially the only one she ever truly loved, Boy Capel. She met him in 1909 while still living with Étienne Balsan, who financed her and got her into the fashion business. She told me she would always love Boy Capel, even though he was never faithful to her. She often shared her feeling that she had wasted her life because she couldn't keep a friend by her side and overcome her loneliness. She once told me, 'It's better to be married to a fat and unattractive man than to be alone.' At one point, she started to rely on me more and more, and although I was flattered, I also wanted to have my own life. Chanel often said that fashion was a business, not an art: 'We don't work as geniuses; we are merchants. We don't hang clothes in galleries to be seen; we sell them.' When we became close, she told me about her German lover, Spatz von Dincklage, whom she had been seeing throughout the war and had accepted as an official partner in 1945. He was 13 years younger than her, and many considered him a German spy, but in reality, he was just a very careless diplomat. Once, Chanel needed his help to get her nephew André out of an internment camp, but he couldn't help her. Spatz was the only German officer she was close with, though he never visited her in uniform. And although there have been rumors and books written over the years that she was a Nazi collaborator, I don't believe it. She just talked too much and sometimes said the wrong things to the wrong people. Chanel told me that during the war, her salon remained closed except for the perfumes, which were still sold at the boutique on Rue Cambon. There were often long lines of German soldiers waiting for the doors to open. Twelve other designers remained in business and continued to sell their collections, including Madame Grès, Balenciaga, and Lucien Lelong, but she stubbornly refused to reopen her salon and work for the Germans. The wife of the Ritz manager once shared with Chanel that she would never forget her shock when Marshal Göring appeared one day with a beautiful, diamond-encrusted pen specially designed for him by Cartier. Chanel was full of contradictions. I adored her, but she was very demanding and expected me to be on call, which wasn't my style. On Sundays, we would go in her chauffeured car to Versailles, where she would run up the small hill to the Petit Trianon to prove how good a shape she was in. She was generous with me; she once offered me a small Picasso painting. She only liked objects because, as she explained, she liked to feel everything with her hands.I was in Milan, at the Principe di Savoia hotel, when Chanel died in 1971. I was devastated to learn that she had died alone, with only Lilou (her long-time assistant) by her side. It later became clear that all her jewelry was missing and has never been found to this day. Lilou was more than a secretary and assistant to Coco—she had managed to keep everyone away from Mademoiselle, including me. Now, I think I know why.’